Accommodate

Bill Culbert, Andew McLeod, Richard Maloy, Allan McDonald, Kim Meek, Rose Nolan, John Reynolds, Marie Shannon, Katy Wallace, Pae White

Curated by Mary-Louise Browne

16 February 2006 - 11 March 2006

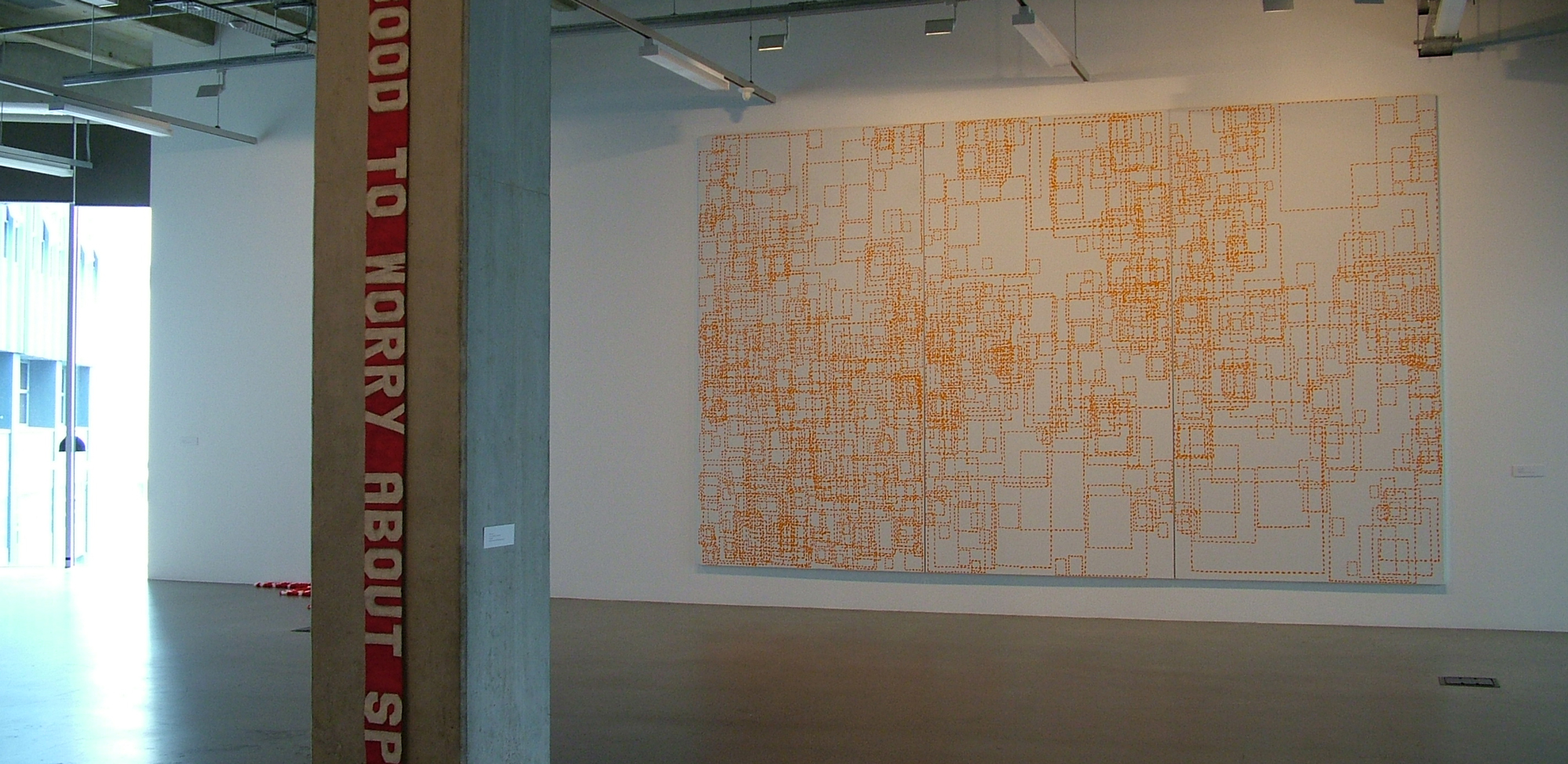

Accommodate (installation view), 2006.

"A capitalist society reduces what is human to the condition of a thing" – Bataille

Many artists in recent years have addressed dialogical aspects of form in relation to human accommodation. Currently, in the hands of art practitioners, the restatement of architecture, furniture and craft as signifier omits standard functionality in favour of slightly more surreal investigations. It is a creative process which creates fresh possibilities for critique. Once referred to as the Gesamtkunstwerk (a singular work of art), one of the precursors to the present content based approach to art was instituted by the coffee house design group, Wiener Werkstatte.

Prior to 1900 most cultures were stuck in the holding patterns of tradition, resisting new advances in art and design in the same manner as later Western institutions. Weiner Werkstatte came about from a feeling of rebellion against the prevailing laissez faire attitudes in turn of the century society. The climate at this time was curiously described by Rudolf von Alt: 'The Vienna Artist spends his life hitting his head against a big grey wall, on which is stuck a heart of blotting paper; the wall is Viennese indolence and the blotting paper heart is the Viennese heart of gold.’ Frustrations notwithstanding, the numerous formal applied design and art groupings of this time provided a sizable quota of impetus for the Modernist art canon that followed.

Unfortunately however, the critical relevance of this slice of history was for many years buried during the male dominated era of austere buildings, heroic art works and belletristic art critics; and by whom the fable of twentieth century Modernism was largely construed. Nowadays it appears that enough time has passed for a revision of the modern era to inspire fresh discourse. The practices in Accommodate offer a diverse range of positions in relation to modern 'isms’ and the notion of accommodate and therefore share several aesthetic inclinations.

The work of Californian artist Pae White is an interesting example. White has been on the scene for several years internationally, notably through having established a contemporary Gesamtkunstwerk type practice amongst some of her generations most interesting artists, via a subversive and critical early project as the graphic designer of artist’s catalogues. Bridging the divide between art and design is a rare feat, and White’s recent work continues to evade categorization. Offering a playful counterpoint to the minimalist fluorescent light installations of Dan Flavin and Bruce Nauman, White’s Fireflys (2005) in Accommodate reside within preserving jars; simultaneously offering a homemade remix on the rubric of the old establishment and yet also reflecting on the detritus of today’s disposable culture.

The light installations of Bill Culbert also offer a counterpoint to art’s status quo. Culbert has explored our hard southern light for many years, establishing a well respected multi-national career. Like Flavin and Nauman, one of Culbert’s primary signifiers is artificial light. In many of his later works, discarded plastic bottles that once held cleaning products are pierced by fluorescent light tubes. The similarly impaled suitcase Petone (1994), for example, is a mordacious take on the transitory nature of Culbert’s travelled art career and which (as Rodney Wilson suggested) also may also imply 'the outcome of romantic ideas about the nature of one’s birthplace formed in youth and nurtured by distance'.

Evoking the recent shift in Auckland’s old red light district from cash strapped bargain shopping into a boutique branded art gallery strip, Kim Meek's Karangahape Jacobethan digital prints have certain local connotations. A direct relative to the politicized and subversive tradition in wallpaper art, Karangahape Jacobethan is reminiscent perhaps of Warhol and more recently the late 80’s wallpaper of artist Robert Gober. You aren’t likely to find Meek selling out to just any cache seeking wallpaper merchant however. This is because layered within the dense patterning of flora, fauna and decorative geometry, a more than cursory glance reveals the more visceral nature of Karangahape road’s “other” business.

Investing into the continuous spread of property development, Andrew McLeod's cosmic looking aerial blueprints of fictional suburban plans suggest surreal clusters of domesticity laid out according to an oblique, divining stick approach to town planning. A reminder of how fleetingly haphazard our social construct often appears, McLeod’s House and Studio (2001/2002) series will never suggest a solution to urban sprawl. Rather, in McLeod’s paintings and digital prints are the implications of our accommodating, temporal desires (e.g. the god complex) made explicit.

The desire to accommodate our temporary and always expanding “I want” lists is captured in the skeletal urbanity of Allan McDonald's House series of 2002. Reflecting on the sprawling masses of suburbia (and potentially leaky homes), House is representative of one facet of McDonald’s ongoing photographic projects. Similar to the cool, detached approach of Walker Evans, the sparse yet elegiac narrative of habitation and property development in McDonald’s series enables each house to transcend the documentary form.

An artist interested in the transitory areas occupied by our varied social stratum, artist Richard Maloy has made an interesting impression. An alternative to the giant coat rack arrangement of affordable Ikea furniture in Guy Ben Nur’s kitset tree house (a hit at the 2005 Venice Biennale), Maloy’s Tree Hut (2004) offers a literally more economic approach than Ben Nur, albeit no less hard hitting. Constructed of found scrap materials from his parents home, Maloy has configured a haphazardly realized domicile. Perhaps cueing the art investor crowd towards a more febrile art experience, at the debut showing of Tree Hut Maloy and his dealer sold slots of time with the artist. Maloy then resided with the paying patrons in his makeshift home for a set duration, like a lady of the night.

Caravan-art maestro Katy Wallace has been busy of late making cardboard reconstructions of everyday furniture and objects. One of the ongoing criticisms of contemporary art is it’s lack of functional purpose. Wallace’s object based art offers a solution, suggestive of the old Marxist dictum, non-abstract labour, making her possibly New Zealand’s best embodiment of a critical materialism (what Nicholas Bourillard has referenced to specifically as art constituting labour itself). Take for instance Wallace’s temporary, corrugated card Wendy House (2005/2006). Wallace provides an innovative and disposable, yet robust play solution, equally suitable for children of indigent status or space cramped city slickers; ready for customization.

In 2001 Marie Shannon travelled with her family to Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. During the course of their ten week stay Shannon (and her son) noted down their temporary surroundings into what for Shannon became an expansive series of small scale watercolours. Shannon is known for her conceptual photographic explorations into aspects of self, filtered through allusions to domesticity. Shannon’s Sketchbook Pages series offer a new insight into her larger body of work. As a highly personal yet operational aspect, through these observations of their accommodation the Gesamtkunstwerk of Judd’s Texas compound and New York Studios is, furthermore, also recaptured with a fresh filter.

Viewing John Reynolds painting Y2K (1999) it is interesting to note that for contemporary painting, despite critical theories which have addressed many aspects, theory usually struggles to accommodate multivalent positions. As is increasingly common with a wide range of critical and aesthetic practices, for a number of years many artists have occupied the same interdisciplinary territory as the cultural studies industry, where theory and creativity have become intertwined. An expansive, gestural canvas, Y2K is the heroic scale of a Pollock, however, the work’s suggestive title and the topographic, hand stitched effect of Reynold’s signature oil stick, evoking a worn out shag pile carpet, as the artist himself has articulated, combine to suggest a critique more densely layered than the sheer scale and paint medium itself is capable of suggesting.

This varied position on art’s content has not always been accepted. As Jonathan Culler, prefiguring our current position (in 1981) observed; 'we should not allow ourselves to forget that theories are not ways of solving interpretive problems, for problems always arise within the framework of a set of assumptions, and a new theory can only challenge or explain those assumptions, not add a supplementary tool to an interpreters toolbox'. Rose Nolan provides a pertinent example of the ever-elusive nature of interpretation. Hand made and self-referential, Nolan’s 2004 rug Not So Sure This Works resides awkwardly on any given floor, intentionally open to a variety of readings. Nolan’s use of humour often grounds references to modernism, fear of failure and domestic feminine narratives. It’s Not Good To Worry About Space, another of Nolan’s recent works, has a comparative effect: This time the work denies itself the chance of a comfortable wall space.